The Story Behind Mass Effect Andromeda's Development

-

Category: News ArchiveHits: 2701

After Mass Effect Andromeda's lukewarm reception, Kotaku's Jason Schreier decided to find out what exactly went wrong during the game's development cycle. He spoke to a number of BioWare employees, who remain anonymous, and produced a lengthy editorial that sheds some light on things. According to the article, the game suffered from multiple changes in the overall vision, understaffed and overworked team, and starting anew basically 18 months before the game was actually released. Here are a few snippets:

I’ve spent the past three months investigating the answers to those questions. From conversations with nearly a dozen people who worked on Mass Effect: Andromeda, all of whom spoke under condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to talk about the game, a consistent picture has emerged. The development of Andromeda was turbulent and troubled, marred by a director change, multiple major re-scopes, an understaffed animation team, technological challenges, communication issues, office politics, a compressed timeline, and brutal crunch.

Many games share some of these problems, but to those who worked on it, Andromeda felt unusually difficult. This was a game with ambitious goals but limited resources, and in some ways, it’s miraculous that BioWare shipped it at all. (EA and BioWare declined to comment for this article.)

Mass Effect: Andromeda was in development for five years, but by most accounts, BioWare built the bulk of the game in less than 18 months. This is the story of what happened.

[...]

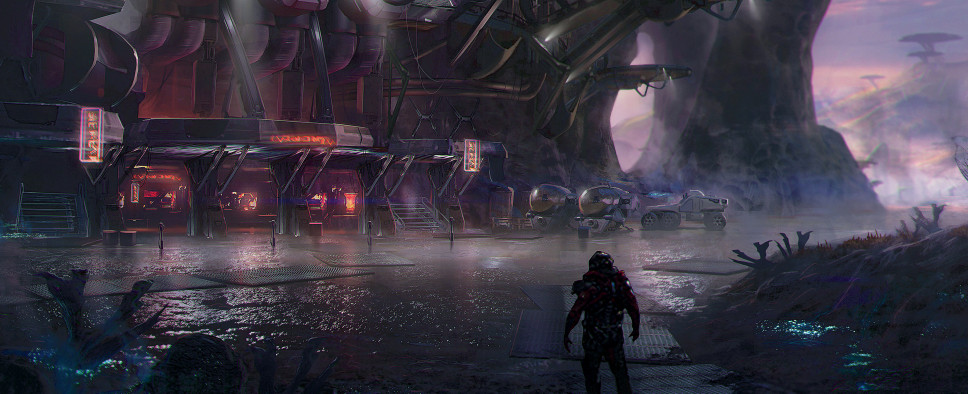

In early conversations throughout 2012, a team of directors in Montreal brainstormed ways in which to make the next Mass Effect that felt distinct. This group, which included several veteran BioWare employees as well as Hudson, who wanted to help guide the project through its infancy, had lots of fresh ideas for a new Mass Effect. There’d be no Reaper threat, no Commander Shepard. They could pick a brand new area of space and start over. “The goal was to go back to what Mass Effect 1 promised but failed to deliver, which was a game about exploration,” said one person who worked on the game. “Lots of people were like, ‘Hey, we never fully tapped the potential of the first Mass Effect. We figured out the combat, which is awesome. We figured out the narrative. Let’s focus on bringing back exploration.’”

One early idea was to develop a prequel to Mass Effect, set during the First Contact Wars of the series’ lore, when the humans of Mass Effect’s galaxy had interacted with aliens for the first time. In late 2012, Hudson asked fans if they’d prefer to see a game before or after the original trilogy. The answers were resounding: most people wanted a sequel, not a prequel.. “The feedback from the community, focus groups and the team working on the project was the same,” said one person who worked on the game. “We wanted to do a game set after the trilogy, not during or before.”

[...]

Lehiany, who wanted to lead the game’s narrative team, came up with several ambitious ideas. One of those ideas became the core concept of Andromeda: during the events of the Mass Effect trilogy, the galaxy’s ruling Citadel council had sent a group of colonists out to a new galaxy to find habitable planets, as a contingency plan in case Commander Shepard and crew couldn’t thwart the devastating Reaper attack. You, the player, would take on the role of Pathfinder, leading the quest to rebuild civilization in the Andromeda galaxy.

Another of Lehiany’s ideas was that there should be hundreds of explorable planets. BioWare would use algorithms to procedurally generate each world in the game, allowing for near-infinite possibilities, No Man’s Sky style. (No Man’s Sky had not yet been announced—BioWare came up with this concept separately.)

Procedural generation is a process that leaves the creation of some of a game’s content to algorithms rather than requiring that each item of the game is hand-crafted. Such a technique could dramatically increase the scope of a space exploration game. It was an ambitious idea that excited many people on the Mass Effect: Andromeda team. “The concept sounds awesome,” said a person who worked on the game. “No Man’s Sky with BioWare graphics and story, that sounds amazing.”

[...]

The Mass Effect: Andromeda team knew they were going to run into major technical barriers with or without procedural generation. Over the past few years, one of BioWare’s biggest obstacles has also become one of EA’s favorite buzzwords: Frostbite, a video game engine. An engine is a collection of software that can be reused and recycled to make games, often consisting of common features: a physics system, a graphics renderer, a save system, and so on. In the video game industry, Frostbite is known as one of the most powerful engines out there—and one of the hardest to use.

Developed by the EA-owned studio DICE, Frostbite is capable of rendering gorgeous graphics and visual effects, but when BioWare first started using it, in 2011, it had never been used to make role-playing games. DICE made first-person shooters like Battlefield, and the Frostbite engine was designed solely to develop those games. When BioWare first got its hands on Frostbite, the engine wasn’t capable of performing the basic functions you’d expect from a role-playing game, like managing party members or keeping track of a player’s inventory. BioWare’s coders had to build almost everything from scratch.

[...]

While describing Frostbite, one top developer on Mass Effect: Andromeda used the analogy of an automobile. Epic’s Unreal Engine, that developer said, is like an SUV, capable of doing lots of things but unable to go at crazy high speeds. The Unity Engine would be a compact car: small, weak, and easy to fit anyplace you’d like. “Frostbite,” the developer said, “is a sports car. Not even a sports car, a Formula 1. When it does something well, it does it extremely well. When it doesn’t do something, it really doesn’t do something.”

“We started to realize by summer 2015 that we had great technological prototypes, but we had doubts they would make it into the game,” said another person who worked on the game. The Andromeda team had gotten systems like spaceflight up and running, two people said, but they couldn’t figure out how to make those systems fun to play. “I think production reality hit hard and they had to make some really strong cuts.”

By the end of 2015, Mass Effect: Andromeda’s leads realized that the procedural system wasn’t working out. Flying through space and landing on randomly generated planets still seemed like a cool concept—and by then, many people at BioWare were looking with great interest at No Man’s Sky—but they couldn’t make it work. So they decided to rescope.

First, word came down that they were moving from hundreds of procedurally generated planets to 30. Some of their terrain would still be generated by WorldMachine and the other technology they’d built, but the content would all be crafted by hand. Some time later, that number shifted again, from 30 to seven, according to several sources. For some teams—design, writing, cinematics—this move led to many questions. “There was that time of, ‘what does this mean for us on the development team?’” said one Andromeda developer. “There was a waiting period of, ‘Well, we’re doing it, so ‘what is getting cut, what’s staying, who’s gonna work on which parts of those?’”